ALL AS ONE

Activists join forces to press premier to deliver promised action on housing

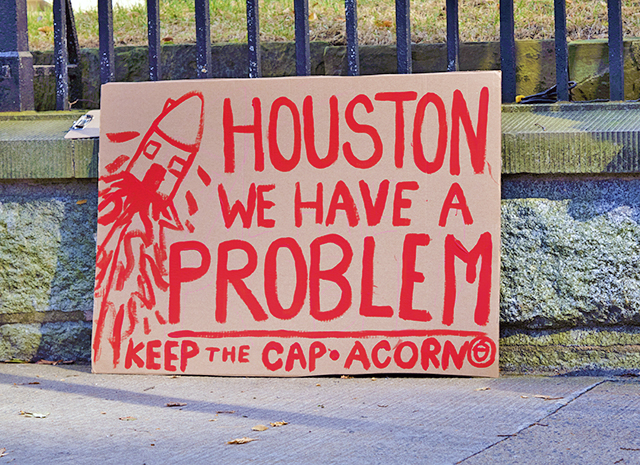

Demonstrator outside N.S. legislature

“HOUSTON WE HAVE A PROBLEM” was the message on one of the placards demonstrators carried outside the Nova Scotia legislature March 21. It was the first day of the spring session and three activist groups had joined forces to remind premier Tim Houston to keep his word to act quickly to make affordable and secure housing available in N.S.

The three groups included:

-

ACORN NS, the Nova Scotia chapter of a Canada-wide movement organizing tenant action among low- and moderate-income people

-

P.A.D.S. Community Network, advocates for rights and secure and dignified housing for homeless people

-

Justice for Workers, advocates for a living wage in N.S.

Three key issues

The demonstrators focused on three key issues: the need for lower rents and affordable housing, the need to strengthen overall tenant protections and an increase in the minimum wage to a living wage.

Rachelle Sauvé, spokesperson for P.A.D.S. Community Network, said the organizations wanted to make it clear issues relating to poverty and housing were widespread and inter related, and the provincial government would have to make changes to everything from housing stock to social support programs to make an improvement.

“It’s the first day of the sitting legislature, and a lot of us are quite concerned by what isn’t in the predicted plan for the year,” Sauvé said. “[P.A.D.S. is] quite concerned that there’s really nothing about housing in the plans that are going forward.

“We thought we would combine forces with other folks who were looking at wage increases and all the other pieces of the puzzle to make a stand and say it’s time for an anti-poverty agenda.”

Lack of affordable housing in the province has been a persistent concern since before the start of the pandemic. In Halifax, the vacancy rate currently sits at 1%; that’s down from 1.9 per cent in 2020.

But since the lifting of Nova Scotia’s state of emergency some emergency protections for tenants are no longer in place. For example, landlords can again evict tenants if they plan to do renovations to their property. Such “renovictions” were banned under the provincial state of emergency.

Organizations that support tenants fighting eviction, like Dalhousie Legal Aid, say they have seen an increase in requests for help since the province lifted its renoviction ban.

Mark Culligan, a social worker with Dalhousie Legal Aid, told the Halifax Examiner: “We have seen a jump in renoviction-related calls. Although I would say that informal renovictions continued throughout the pandemic.”

In order for a landlord to evict a tenant, Culligan said, there are processes they’re supposed to follow. The problem, Culligan said, is that a lot of tenants don’t understand their rights.

“Often landlords tell people they just have to leave.” Culligan said. “That happened throughout the pandemic. That stuff isn’t going to show up in the court records, because it wasn’t legal to do that. But people were doing it anyway.”

‘No proof in the pudding’

Hannah Wood spoke for ACORN NS at the rally to raise concerns about the roll back of rent controls, now that the province has lifted the state of emergency.

“[Rent control] definitely saved hundreds of people from homelessness,” Wood said. “But [the province has] already started to roll back elements of it, so that less people are protected.”

“Tim Houston’s government has been very firm that they believe there’s a market solution to this problem, and that we can build our way out of it,” Wood said. “But there is no proof in the pudding.”

Wood said that while more apartments are being built, rents are not coming down. Currently, the average price of a one-bedroom apartment in Halifax is upwards of $1,600 per month—more than half the monthly take home of a minimum wage worker working 40 hours a week.

Labour and housing connected

But increasing the availability of housing is only one piece of the puzzle, says Suzanne MacNeil, spokesperson for Justice for Workers. For her the “housing problem” is also an “income problem.”

She points out low wages and high rents were problems in Nova Scotia long before the pandemic began. If the province can’t or won’t control rents, it will have to raise wages, she says.

Justice for Workers is advocating for a $20 an hour minimum wage in Nova Scotia and 10 paid sick days for workers annually. In November 2021, a report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives estimated Halifax’s living wage at $22.05 an hour—almost double the $13.35 per hour it is now.

“The issues around workers’ wages and working conditions, around housing, tenants’ rights and homelessness, and around poverty — they’re all connected,” MacNeil said.

- 30 -

Add new comment