TENANT UNIONISM

THE RSB MODEL: Union power at work. Union power at home.

The RSB campaign

THE RENT. STRIKE. BARGAIN. (RSB) Campaign aims to build power through solidarity between tenants and labour across British Columbia, with the ultimate goal of winning the right for renters to collectively bargain & form tenant unions.

What follows are edited excerpts from an interview with RSB conducted by Rankandfile,ca. The full interview is available at https://www.rankandfile.ca/rent-strike-bargain/.

RSB’s prime objective is to win collective bargaining rights for tenants in British Columbia. What brought RSB members to your conclusions about the need for tenant collective bargaining?

Some of our early members came across the article Tenant Organizing and the Campaign for Collective Bargaining Rights in British Columbia, 1968–75 by Paul S. Jon, which described the BC tenants’ movement and a campaign for collective bargaining in the late sixties to mid-seventies.

The ends are the means

What was so powerful about that campaign was that its ends (winning collective bargaining rights for renters) were also its means (organizing for power through tenant unions). However, the BC renters’ movement was different then, and more rural tenant unions already existed. Connecting with this history, we were inspired to create our own three-pillar platform for empowering tenants to act collectively to protect their homes:

Three-pillar platform

[1] Fostering Tenant-Labour Solidarity

[2] Seeding new Tenant Unions across the province

[3] Achieving Collective Bargaining Rights for Tenants

Many of our members have backgrounds in both tenant and labour organizing. In organizing the campaign, we found that there was quite a bit of interest in exploring how these two working-class movements could mutually strengthen each other to pursue their own goals. What we realized in planning the campaign was that a provincial drive to start up new tenant unions would need provincial partners that were democratic and led by local members.

Unions endure

While some tenant unions have vanished over the years, labour unions still exist in even the smallest of towns and have helped us to get in touch with working-class people who already had some idea, through participation in labour unions, of what collective bargaining and organizing could do for renters.

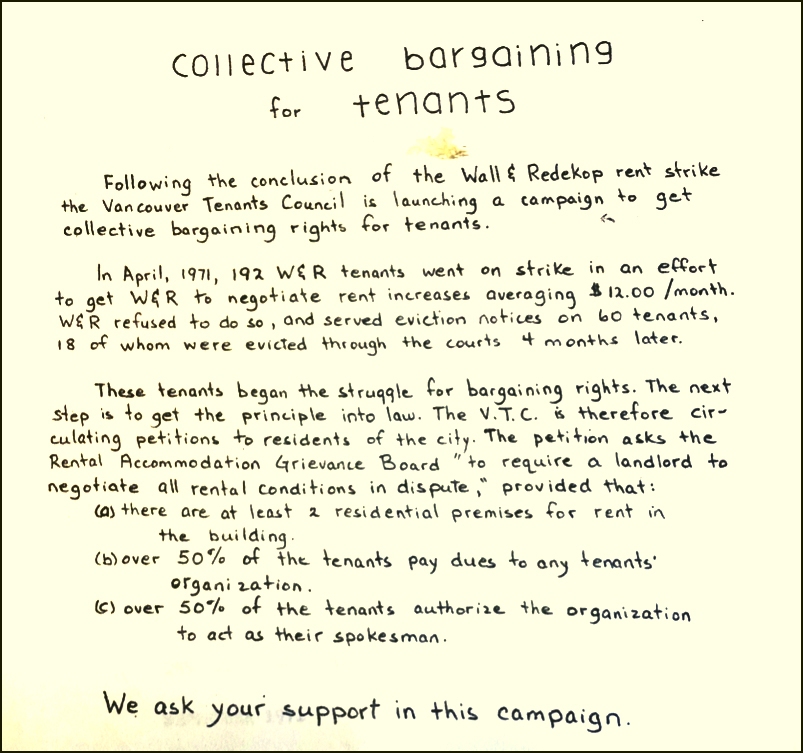

A proposal for how tenant collective bargaining was proposed for one building in Vancouver in the 1970s

Can you sketch out what this collective bargaining process might look like? Are there examples from Canada or around the world that we can look at and learn from?

Our definition of collective bargaining for tenants includes three key pillars: organizing, negotiation, and collective action, including strikes.

Organizing

First, we believe tenants must have the right to organize, including the right of access to union organisers into their buildings, and explicit protections against retaliation for organizing. We envision a process where tenants can join together, either building by building or across buildings owned by the same landlord, to act collectively to make demands of their landlords, including demanding and bargaining collective leases.

Negotiating

Once a majority of tenants wish to bargain collectively, the landlord would have no choice but to recognize the union and engage in good faith collective bargaining. For tenants in basement suites or those renting in single family homes, we envision a kind of block or sector unionization structure, where tenants can bargain together or at the same time with their landlords.

Collective action

Lastly, but very importantly, we want the right to strike, without fear of losing our homes.

While there are examples where tenants have already engaged in collective bargaining by making demands and taking collective action without the law clearly providing support for their actions, there are very few examples of formal, legally supported processes for tenant collective bargaining in the world.

Right to collective bargaining in Sweden

One example of legally recognized tenant collective bargaining exists in Sweden. The Swedish legal framework is a highly bureaucratized process, with the tenants’ union existing as a nationwide body, and local rents negotiated through what they refer to as a “utility-value formula” (which considers things like the state of the apartment and the desirability of the neighbourhood). Though not what we want here, the Swedish system does include a legal process for tenants to dispute the negotiated rental rate if they wish.

In other jurisdictions, the closest we have is legislation that confirms tenants’ rights to organize tenant unions or associations.

Right to organize in Ontario

In Ontario, for example, provincial legislation expressly recognizes that evictions for organizing are without cause and that harassment of tenants for organizing or interference with tenant organizing is illegal.

Legal provisions recognizing the right to form tenant unions led the Landlord and Tenant Board to grant an extended length of time to a COVID-19 rent repayment plan, where a landlord refused to negotiate a repayment plan with a tenant’s union.

Right to organize in Manitoba

Another provincial example is in Manitoba, where legislation protects against landlord intervention in the formation of a tenants’ union and makes it illegal for a landlord to prohibit the use of common areas for tenant union meetings.

In contrast to these protections and rights, BC does not have any provision in any legislation recognizing the right of tenants to form tenant unions or associations.

Union collective bargaining model

While there are not many existing formal processes for tenant unions to look to, there is a long history of labour union collective bargaining that can be looked to for guidance–and for caution.

This includes the many court challenges fought by labour unions to establish Charter rights for workers to organize and collectively bargain. There are differences between the landlord-tenant and employer-employee relationship, and what collective bargaining looks like for tenants will not be exactly the same as it does for workers. But it is a place to start.

However, we strive for more limited intervention in tenant collective bargaining than the existing legal process for trade unions and labour collective bargaining, which we see as placing too many limits on trade union organizing, collective bargaining, and striking-and, in solidarity with the labour movement, we hope for more limited intervention in trade union bargaining, too.

RSB has the formal support of the Vancouver District Labour Council, Unite HERE Local 40, CUPE Local 15, and the Teaching Support Staff Union at Simon Fraser University. How was this support achieved?

Not only them, but also the Vancouver Tenants Union, New West Tenants Union, CUPE 3338, BCGEU Local 304, BCGEU Local 306, the BCGEU’s Provincial Executive, and the Vancouver Elementary School Teachers Association (VESTA)!

Union endorsements

Our union endorsements are some of our most proud achievements.

We started by reaching out to institutions that had either long signalled their support for the renter’s movement or who we believed had a significant renter contingency in their membership. From there we ask to either present to their general membership, or to their elected executive for an endorsement, dependent on the union’s endorsement procedures. Since many of us are unionized workers, we used the democratic processes within our unions to seek support. The Vancouver District Labour Council (VLDC) was the first labour body to endorse the campaign and from there word spread quickly.

So far, our biggest endorsement has been the BCGEU Provincial Executive, whose solidarity and support have been key to the campaign’s organizing efforts, but we are incredibly thankful to all of the labour leaders and unions who have supported us so far.

Working the territory

The real organizing and solidarity work, however, starts after the official endorsement. When we ask for an endorsement from unions, we also ask unions to distribute our Workers Who Rent survey, which seeks to identify renters within existing unions.

From there we divide the survey respondent data by region and rank the leadership potential of those renters who selected that they would be interested in getting involved using a system we’ve developed internal to the campaign.

After this step has been completed, an organizer from within the survey respondent’s Regional Pod reaches out to renters who have consented to get involved in the campaign. Once a Regional Pod has reached a large enough size, we move into helping them launch an official Tenants Union for their city or region.

Solidarity model

Lastly, from a governance perspective, our campaign is largely modelled off of the Solidarity Coalition, one of the largest protest movements in BC history. The movement was made up of tenants, labour, and community activists who all came together in the 1980s to oppose widespread government cuts and austerity. Like Solidarity, we ask that all unions and community groups who endorse the campaign send a representative to sit on one of our working groups.

RSB works with local tenant groups. How does that work?

Participatory governance

Similar to labour unions, after receiving an endorsement from a local tenant group or a tenant union (meaning a democratic, member-driven renters’ organization) we ask them to send a representative to help govern RSB. In being their RSB representative, this member oversees reporting back to their local tenant union, communicating ways in which the campaign can support their local, and asking their local for support when the campaign needs it.

In places where we have a sizable number of renters identified through our Workers Who Rent survey and where a tenant union already exists, we work with the local tenant union to get our volunteers in the regions activated and involved in their organisation. We do this through phone banks and advertising the local union’s events.

- 30 -

Add new comment