No Dice On Ice

It takes money to make the NHL

ANNA AND BOBBY HANNAH HAVE THE MONEY. They make a good living with their sign business in Dieppe, New Brunswick. So, they’ll make the drive to Tuscaloosa, Alabama two or three more times before hockey season is over. They’ll go to watch their son Jeremy play for the University of Alabama hockey team. The drive is almost 3,000 kilometres one way. It takes 26 hours. It doesn’t matter. It’s to support Jeremy.

Anna and Bobby have been doing things like this, and a lot more, for Jeremy since he was six years old and got serious about hockey. They laid out for hockey camps, the best skates, sticks, equipment, spending money, trips to support him when he played in the Quebec junior league. They could afford it all and were happy to spend it on him. Anything to make Jeremy’s dream of playing in the National Hockey League more possible. Without that spending Jeremy would have next to no chance.

Jeremy’s hockey skills wouldn’t matter. His work ethic wouldn’t matter. His average points per game wouldn’t matter. Nobody would have ever seen any of it without his parents ability to spend money to ‘keep him in the game.’

Staying in the game, going from a teenage Sydney Crosby endlessly shooting pucks at his mum’s clothes dryer in the basement in Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia, to scoring leader in the NHL, takes boatloads of natural talent and relentless hard work. It also takes a lot of money. Something a lot of talented kids don’t have.

Income inequality haunts hockey rinks

Playing hockey at any level above house league has become a luxury that fewer and fewer in Canada can afford. The Winnipeg Free Press reported that the tab for playing elite hockey for kids from 8 to 13 can run well over $20,000. Some young hockey players are wearing skates that cost almost $1,000 and their hockey sticks are $300 a pop.

A secret survey by Hockey Canada confirmed that poor kids never go on to play major junior, college or pro hockey. The survey of 1,300 parents found that average household income was roughly 15% higher than the national median. The majority listed their occupation as a “professional, owner, executive or manager,” a reflection of hockey’s new white-collar base.

Playing hockey, even at lower and entry levels isn’t cheap. The Hockey Canada survey showed that the average hockey parent spent just shy of $3,000 on minor hockey in the 2011-12 season alone. Those costs included $1,200 for registration and ice time, $900 for travel and accommodations and more than $600 for skates and other equipment. As their children got older the seasonal costs almost doubled. Parents paid out about $3,700 a season, for children between the age of 11 and 17.

The fact is that poor kids will not likely end up in the NHL. A handful might, but the odds and the system are heavilty stacked against them.

Money talks, poor kids walk

Here’s the reality. All kids can play hockey at the very basic and beginners levels. There are many types of supports that are available to help both boys and girls get a pair of used skates, a jersey and the very minimum equipment. But once the hockey moves into competitive areas and leagues, money talks and the poor kids walk.

There is almost no support to help gifted hockey prodigies pay for things like composite hockey sticks, spring and summer hockey schools or leagues where players and their parents have to pay fees for ice rental and thousands of dollars to sign and travel with a competitive team.

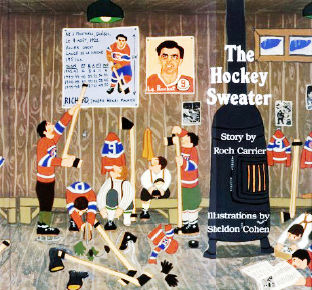

The Hockey Sweater by Roch Carrier

A story so Canadian we printed these words from it on our five dollar bill:

“The winters of my childhood were long, long seasons. We lived in three places – the school, the church and the skating rink – but our real life was on the skating rink.”

The money that is available from various levels of government goes into organizations like Hockey Canada which funnel these dollars into elite training programs to support the development of high-performance or national team athletes. In 2014-15, the federal government gave Hockey Canada nearly $5.4 million. More than $4 million of which went into the elite programs. Hockey Canada does give some money back to communities but they are small and scattered initiatives like a few outdoor skating rinks and some equipment funding.

Provincial funding is even more meager. For example, Ontario earmarked

nearly $720,000 for hockey in 2016-17. Of that, $367,000 went to the Hockey Development Centre for Ontario, which co-ordinates and distributes funding to the province’s amateur hockey organizations. When you break that down, it amounts to roughly $1 per player per year. That’s not enough to buy a pair of skate laces.

Hockey used to be a symbol of what was right about Canada. What defined and united us. Now it’s just another example of the gulf between us, between those who can afford to pay to play, and those who can’t.

Add new comment