WORKED TO DEATH

Failure to bring criminal charges may let bosses ‘get away with murder’

Olivier Bruneau was crushed and killed on the job in Ottawa in 2016

WHO’S FAULT IS IT THAT JESUS SANCHEZ IS DEAD? Nobody asked that question in 1996. Now Oliver Bruneau is dead too.

There should have been an inquest 20-some years ago when Jesus Sanchez fell 13 metres to his death on the job. Ontario law makes it mandatory. But there was no inquest. Nobody can say why.

That fact torments Christian Bruneau every day. His 24-year son Olivier was killed at a construction site in Ottawa on March 24 2016. He was crushed by a slab of falling ice. Olivier was working for Bellai Brothers, the same company that Jesus Sanchez worked for when he was killed at work in 1996.

Christian Bruneau can’t help thinking: “Maybe Olivier would still be with us if there had been an inquest back then.”

Bellai Brothers and two of its supervisors face civil charges relating to Olivier Bruneau’s death. Clarridge Homes, the company which ran the site where Olivier Bruneau worked, has also been charged.

A closer look at Bellai Brothers discovered the company had been charged and convicted of labour safety violations contributing to Jesus Sanchez’s death.

The court ruled that “none of the defendants have shown anywhere near the amount of diligence that could be considered reasonable and due.” Bellai Brothers Construction among others, were convicted and fined.

Yet at the time, a coroner’s inquest was never held in Jesus Sanchez’s death—a fact that contravenes Ontario’s Coroners Act. That meant that the firm was never probed for systematic safety violations. It took the death of Olivier Bruneau, for that to happen.

Justice delayed is justice denied

It took 20 years, but the coroner has announced there will finally be an inquest into Jesus Sanchez’s death—but not any time soon. The inquest into Christian Bruneau’s death has already been delayed until after May 2019. Such delays do not speed justice or soothe the heartbreak for the families of the dead workers.

“As a family, the delay adds insult to injury,” says Christian Bruneau.

“The injury is the damage they did to my family, with Olivier who died. Then the insult is to say, ‘Well, I’m not available before May 2019 to go to court.’”

“My son is dead and I have to wait more than three years to find out what happened. To mourn in such a situation is very difficult,” Christian Bruneau said.

The long delay for a court date also affects other investigations into the death. A coroner’s inquest cannot be held until the court case is complete. Similarly, a Ministry of Labour report into the death cannot be provided to Bruneau’s family until after the trial.

‘You can’t call these events accidents’

The fate of Jesus Sanchez and Olivier Bruneau is far from exceptional.

One worker dies on the job, on average, nearly every day in Canada, according to the Association of Workers Compensation Boards in Canada. Add the cancers and longer-term illnesses from occupational exposure, and the number climbs to nearly 1,000.

But there is no really accurate national data on workplace injury and death because there is no coordination among our provinces who have jurisdiction over all labour relations in Canada.

“I don’t think people generally have an appreciation of just how dangerous work is,” says Steven Bittle, associate professor of criminology at the University of Ottawa, who is working on a project to estimate the actual number of people who are killed at work each year, beyond the workers’ compensation numbers.

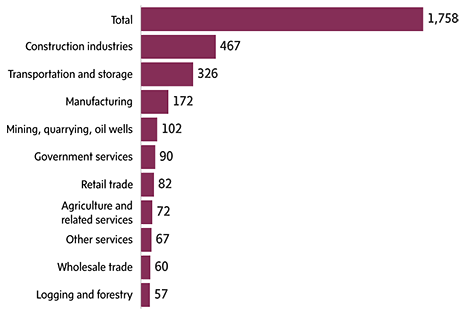

The 10 industries with the highest number of traumatic injury fatalities, 2011-2015

On-the-job deaths often have legal implications, he added. “You can’t call these things accidents. People knew or should have known, or were required to know, and nothing was done about it and the consequence is that somebody died.”

Other Canadian studies have found that up to 40 per cent of eligible injury claims are not reported to workers’ comp boards. As a result, workplaces seem safer than they actually are.

A quick look at some of the incidents of workplace fatalities recently reported by the media in Canada gives a grim snapshot of the reality of life and death on the job in Canada:

- November 1: A construction worker fell eight metres to his death from a balcony at an apartment construction site in the south of Edmonton

- November 8: A worker was killed at the Canada Pacific Rail yard in Cote-St-Luc in what was described as a “rail accident.”

- November 11: A man was crushed and killed by a truck at an industrial yard in Mississauga

- November 25: A worker at the Lafarge precast concrete plant in east Edmonton was crushed to death under concrete

- December 5: A worker was crushed to death in Mississauga when the forklift he was using to deliver construction equipment tipped over

- December 8: An industrial painter in Acheson, Alberta, died after falling from the top of sandblasting equipment while working on a tower crane

- December 14: Four Hydro One workers were killed in a helicopter crash in eastern Ontario

- December 19: One worker died and five were seriously injured in a suspected incident of carbon monoxide poisoning at a repair facility west of Edmonton

- December 22: A 26-year-old Canadian National Railway worker was killed while she was performing routine maintenance at the Melville rail yard in Saskatchewan

- January 6: 52-year-old Deepkiran Singh Gill was killed in unclear circumstances at the Richmond Plywood Corporation in Richmond, BC

Criminal activity

CBC found that in over 250 cases of worker deaths that have occurred since 2007, courts only issued five jail sentences with a maximum sentence of 120 days behind bars. In cases involving fatalities, the median fine for employers is a pitiful $97,500.

Patrick Desjardins was just 17 years old in 2012 when he was killed on the job at a Walmart in Grand Falls, NB. He was electrocuted while using a second-hand floor polisher the store bought at a yard sale. Walmart was fined $120,000 for negligence leading to Patrick’s death.

Video surveillance showed the polisher was not plugged into a grounded outlet. When shocked Patrick’s knees buckled, he grabbed the cord and fell onto his back on the wet floor. The polisher fell on top of him and he suffered electrical shock for about 25 seconds before he stopped moving

The small fine enraged Patrick’s father:“Walmart can earn $120,000 in 15 seconds. It’s trying to put a price tag on my son and you can’t do it … Those fines should be increased, big time.”

As well as heftier fines, workers and unions are demanding more criminal prosecutions.

Last March, the United Steelworkers marked the first anniversary of Olivier Bruneau’s death with a renewed call for criminal prosecutions for death on the job. “We have been down this road before and we know Ministry of Labour charges are not enough to hold corporations criminally accountable for killing workers,” Marty Warren, the Ontario director of the USW, said.

Unions continue to press for better enforcement of the Westray Law: legislation passed in reaction to the 1992 Westray Mine disaster where 26 workers were killed in an explosion.

The 2003 law provides for criminal charges to be brought against corporations, their representatives and those who direct the work of others in the event of injury or death on the job.

The Westray Mine Disaster Monument sits in a park in New Glasgow, NS at the approximate location above ground where the bodies of 11 miners remain trapped. The memorial’s central monument is engraved with the names and ages of the twenty-six men who were killed in the disaster, along with the message: “Their light shall always shine.”

Add new comment